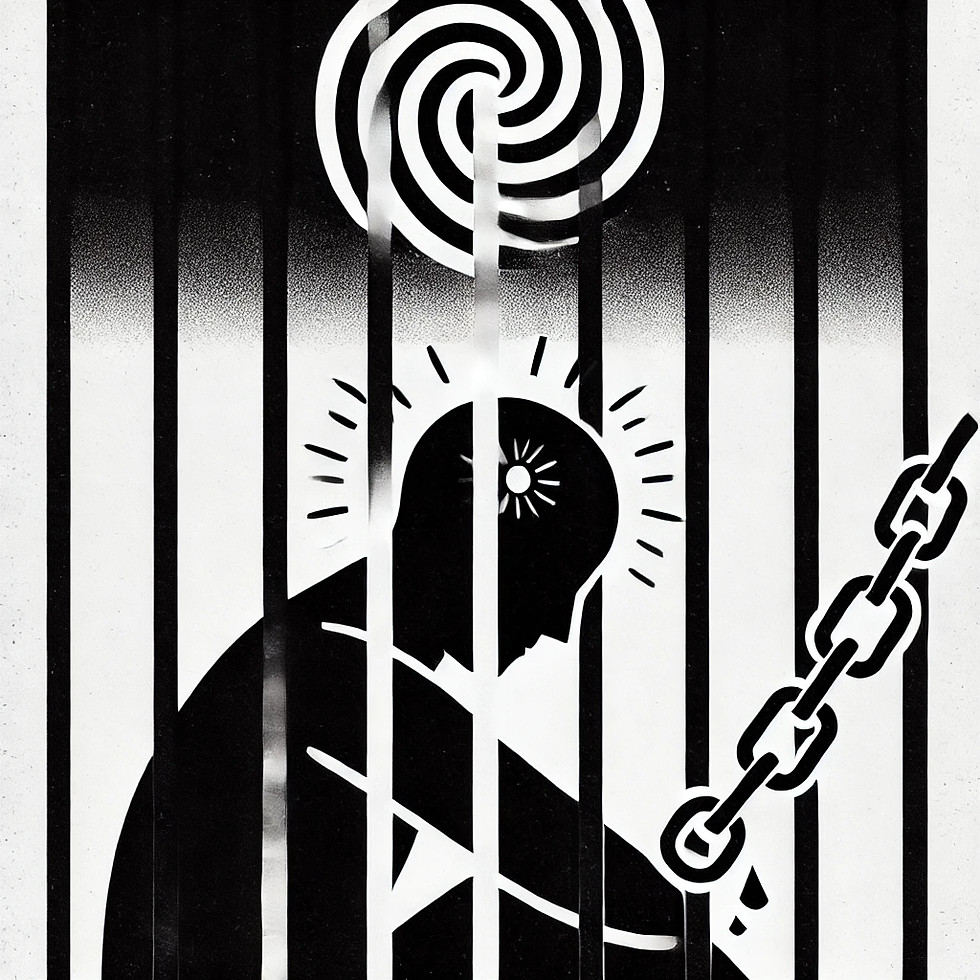

Mental Health and Trauma: The cycle of incarceration and untreated trauma

- Swop Behind Bars

- May 9, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 14

Keisha had been in and out of the system since she was 16. Her record listed drug possession, petty theft, loitering—but what it didn’t say was that she'd been surviving childhood sexual abuse, a violent partner, and years of housing insecurity.

When she was arrested again at 34, after missing a court date for shoplifting diapers, she told the intake nurse she had PTSD. She mentioned the panic attacks, the insomnia, the nightmares.

They handed her a pamphlet and told her to put in a “kite” if she wanted to talk to someone. She did—three times. No one followed up.

Weeks later, during a flashback episode, Keisha banged her fists against the wall of her cell, screaming for help. She was pepper-sprayed, thrown into solitary, and written up for "threatening behavior." She spent seven days in isolation.

What Keisha needed was trauma-informed mental health care. What she got was punishment.

The Cycle of Incarceration and Untreated Trauma

For many incarcerated women, jail or prison isn’t the beginning of a crisis—it’s the continuation of one. Behind the statistics of who ends up behind bars is a stark and painful truth: most incarcerated women have experienced serious trauma long before they ever committed a crime.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, approximately 75–90% of incarcerated women have experienced physical or sexual violence, and many are living with PTSD, depression, anxiety, or substance use disorders stemming directly from those experiences. But inside jails and prisons, trauma is rarely met with treatment—instead, it's often met with isolation, discipline, or neglect.

Incarceration as Trauma

Being locked up is traumatic in and of itself. For women—especially those with histories of abuse—strip searches, restraints, surveillance, and the loss of autonomy can mirror past violations and retrigger PTSD.

Facilities often lack trained mental health staff, and even when services exist, they're usually crisis-based and reactive, not ongoing or therapeutic. Instead of receiving care, women with mental illness are often:

Placed in solitary confinement for “acting out” or self-harming

Denied medication or given the wrong dosages

Written up for behaviors rooted in trauma responses like withdrawal, dissociation, or hypervigilance

This system turns trauma into a disciplinary issue—further punishing women for the pain they've carried into the system with them.

The Criminalization of Coping

Many women enter the justice system not despite their trauma, but because of it.

Survival behaviors like sex work, substance use, theft, or running away are frequently criminalized rather than understood as symptoms of untreated trauma or poverty. Instead of access to mental health services, women are handed criminal records—and the cycle begins again.

The same system that denies them healing turns around and punishes them for how they’ve tried to survive.

Who Pays the Price?

Women of color, trans women, poor women, and women with disabilities are the most impacted. They are also the least likely to have access to stable, community-based care outside the system—meaning incarceration often becomes the only place they receive any services at all, even if those services are deeply flawed.

The results are devastating:

Increased rates of self-harm and suicide

Deteriorating mental and physical health

Loss of child custody, housing, and support networks

Greater risk of recidivism upon release

And all of this happens in silence, tucked away from public view, behind steel doors.

Breaking the Cycle

If we are serious about ending mass incarceration and building a more just society, we must center mental health and trauma in our response—not ignore it.

That means:

Funding trauma-informed care in jails, prisons, and reentry services

Ending the use of solitary confinement for women with mental health needs

Decarcerating women whose behaviors are rooted in trauma, addiction, and mental illness

Creating community-based alternatives to incarceration that prioritize healing, not punishment

Training correctional staff to respond to trauma with care—not control

A Future That Heals

Keisha’s story is not unique—but it doesn’t have to be inevitable. We have the knowledge, the tools, and the models to do better. What’s missing is the political will and public urgency to act.

Because no one should be punished for their pain. No one should be locked in a cell for needing help. And no one should be told that survival is a crime.

Next in the Series

In our next post, we’ll examine what happens after incarceration, and how the trauma and neglect women experience inside impacts their ability to rebuild their lives outside. From health care access to housing to parenting, we’ll explore how our systems keep women trapped even after release—and what it takes to break free.

Comments